Grocery Store Tours are an Effective Way to Provide Nutrition Education to Low Income Minority Populations

CURRENT RESEARCH IN DIABETES & OBESITY JOURNAL JUNIPER PUBLISHERS

Authored by Christina Ralston

Abstract

Objectives: The objective of this study was to provide nutrition education via grocery store tours to improve the nutrition knowledge of the participants and to foster positive behavioral changes to decrease the incidence of obesity and its' related diseases such as diabetes and hypertension in the Memphis community. According to the Health Belief Model, providing "cue to action” in the form of nutrition education will bring about positive behavior change.

Methods: Participants attended a 90 -minute grocery store tour and discussion and completed a 10- question survey at the end of the tour. The surveys were analyzed for participants learning and anticipated behavioral changes. Numeric answers on the survey were totaled as a percent of the total answers and open- ended questions were analyzed using semantic content analysis.

Results: Prior to the tours, participants (n=125) reported eating fewer than the recommended servings of fruit and vegetables per day (78%). However, 88% reported that they would increase their intake based on

Conclusions and implications: Grocery store tours proved to be an effective method of providing nutrition education for adults. This supports the Health Belief Model that procing "cues to action” does bring about behavior change. By understanding proper nutrition, participants may be able to avoid obesity and its related co-morbidities.

Keywords: Education; Nutrition; Grocery store tours

Introduction

The state of Tennessee has a high rate of adult obesity (33.8%) and adults who are overweight (34.9%) in comparison to other states [1]. Tennessee's high school students have the second highest rate of obesity (18.6%), in the nation [1]. Obesity is linked to high rates of hypertension (38.5%) and diabetes (12.7%) [1]. Furthermore, an increased rate of heart disease, arthritis, and obesity-related cancers are more prevalent in Tennessee. Poor diet contributes to increased medical costs as overweight individuals spend more on healthcare each year than their non-overweight counterparts. Memphis has the highest obesity rate of any city in the US. Memphis has a high (63%) African American (AA) population and AAs have a higher than average rate of obesity and diseases associated with it. In the US, non-Hispanic blacks make up 48% of obese individuals [2]. Additionally, Memphis has a high poverty rate (26.2%) and residents may lack an understanding of how to eat healthy on a budget. Lack of education about proper nutrition, the ability to incorporate healthy options into their diet and the knowledge of healthy food preparation, may contribute to the high rate of obesity among AAs. Proper nutrition education is essential for those who want to eat healthy, lose weight, reduce blood pressure and glucose to avoid heart disease and premature death. There are several models that explain why an individual would or would not act to improve their health.

Accordingtothe Health BeliefModel, there are three components to behavior change; an individuals' perceptions of the likelihood of getting a disease, the modifying factors and the likelihood of action [3]. In the first component, an individual’s perceived susceptibility to the disease and the perceived seriousness of the disease are considered. In the second component, modifying factors, demographic and sociopsychological variables and cues to action (outside influences such as education) are considered. These modifying factors along with individual perceptions result in the third component, the likelihood of action, which means the likelihood that a person will act to prevent the "disease.” Therefore, nutrition education should address the individual perceptions of the disease (percent of AAs who are obese, have diabetes, etc.) and the modifying factors (education on prevention and treatment via education). According to the model, when these two components are addressed, behavior change will be the outcome.

Other evidence supports the hypothesis that proper nutrition education produces a positive behavioral change. Rustad and Smith offered three nutrition education sessions with presentations, demonstrations and activities to 118 low- income women (ages 23-45) at various community settings [4]. The education sessions contained pre- and post-tests pre- and post-test to evaluate comprehension and behavioral changes. The researchers detected improvements in nutrition knowledge and favorable nutrition behavioral changes based on pre- and posttest answers (P <.05). These authors concluded that short term nutrition education provided to women on their level does brings about positive behavioral change.

In 2009, a telephone survey of WIC participants in California determined that improved nutrition awareness and positive behavioral changes resulted from nutrition education [5]. After receiving nutrition education about fruits and vegetables, whole grains, and lower-fat milk, the survey respondents reported improved awareness of the value of whole grains, low fat dairy, and increased color variety in fruits and vegetables, as well sometimes” foods such as desserts and fried foods. Improvements in family consumption of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and low-fat dairy were positive behavioral benefits of the study.

Nutrition education may assist people to live healthier, but many people don't have access to proper nutrition education or can't afford to consult a registered dietitian. Due to the demand for an intervention to end the cycle of obesity in the Memphis community, the University of Memphis (UM) nutrition department has taken great strides to educate the city. The initiative UM has taken includes education on healthy eating habits and ways to revamp the way the public shops for groceries. Additionally, education is provided on the causes of obesity related diseases and exactly how diet effects these diseases and the incidence of obesity and its’ related diseases in the AA population of Memphis. One to two times a month, grocery store tours are held at local supermarkets to educate the public on smart and healthy ways to shop for food. These group tours are hands-on strolls through the stores, which allows everyone to participate and learn from the dietetic intern in an informal setting. The purpose of this study was to determine the efficacy of providing nutrition education, in the form of grocery store tours, to improve the nutrition and disease knowledge of the participants and to foster positive behavioral changes, to decrease the incidence of obesity and its' related diseases, such as diabetes and hypertension, in the Memphis community.

Materials and Methods

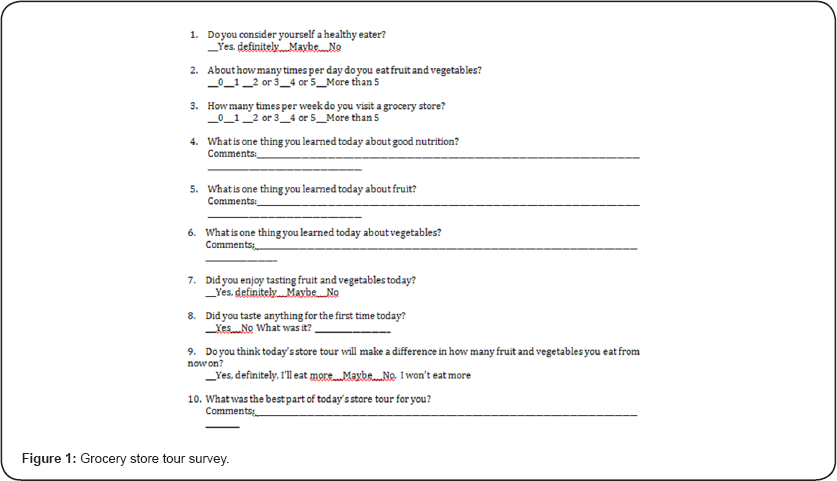

Starting in January 2015, dietetic interns began to provide grocery store tours for people in low income areas of Memphis.The tours focused mainly on increasing fruit and vegetable intake, although healthier options from each area of the grocery store were discussed. The tour guide led the participants through the grocery store and described the healthier items in each area, such as hydrogenated vegetable oil vs olive oil and processed cheese vs natural cheese. Participants in the tour were provided with specific food items food items to taste and they were asked to complete a 10-question survey at the end ofthe tour Figure 1. No demographic data were collected. At the end of the tour, participants entered a drawing to win a prize. All prizes were related to food and nutrition, such as kitchen towels, pot holders, and measuring cups and spoons. Interns were trained in compliance with the Grocery Store Tour Training Kit [6]. A training session was held in the fall of 2014 and every August thereafter, for to account for new interns. Interns conducted the tours on Saturday mornings, in pairs and provided tours to 5 stores in lower income areas of Memphis and 1in North Mississippi.

Grocery store tours were advertised at the public libraries and surrounding businesses in 5 areas of Memphis and 1 in North Mississippi. The program director and her graduate assistant for the project also spread the word by appearing on two Memphis television stations and one radio station every fall and spring. In February 2017, the local newspaper, Memphis Commercial Appeal, published an article about the tours. Although the tours were targeted to AAs, they were open to everyone and the tours were free of charge. The study was exempt from Institutional Review Board approval at the University of Memphis. Tour surveys were analyzed to determine the outcome of the program. The numeric answers were totaled and expressed as a percentage of the total. Tour participants were asked open ended questions about what they learned from the grocery store tour and the responses were analyzed using semantic content analysis [6]. Procedural steps for content analysis of open ended questions were as follows: Participants' responses were read by the program director and by a research assistant separately to look for overall themes and patterns. Using inductive analysis, common themes, patterns, and categories were generated and identified. These common themes, patterns and categories were assigned code words, and these code words were approved for use in the analysis [7]. The researcher and research assistant independently read and identified significant statements in line-by-line analysis, using the approved codes. Coded segments were matched for rater reliability. Frequencies of themes, patterns, and categories were calculated and by various identifiers.

Results

A total of 125 participants from January 2015 to March 2017 took part in a grocery store tour. Some participants didn’t complete the entire survey or provided multiple answers for a single question. Thus, the sample sizes of tables differ. Survey results revealed that only 33% believed they were healthy eaters and only 22% reported eating the recommended 4-5 fruits and vegetables a day. Because of the tour, 88% planned to increase their fruit and vegetable consumption.

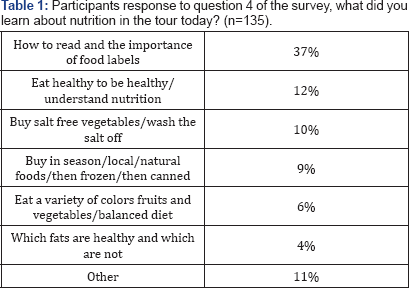

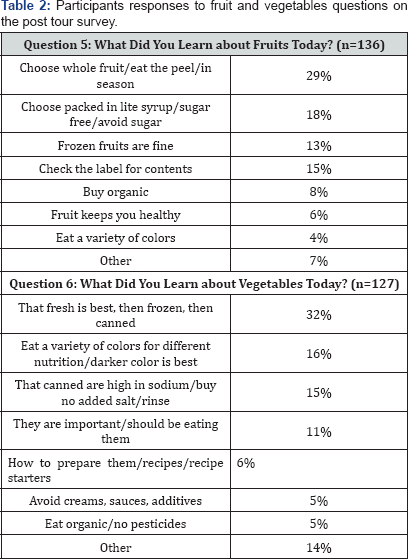

The following themes arose from the coded segments of the question, what did you learn about nutrition today: food labels, be healthy, reduce salt intake, buying fruits and vegetables, balanced diet, fats. When asked specifically what they learned about fruits and vegetables, more specific themes arose. Table 1 & 2 show the results of the three open-ended questions about participant learning with the themes and percentages for each theme. Table 1 shows the overall nutrition learning outcome from the grocery tours. Thirty seven percent of the participants stated they learned the importance of food labels and how to read them. Table 2 displays increased awareness among the participants concerning fruits and vegetables. Twenty nine percent learned how to choose and eat produce, as well as the seasons for certain fruits. Thirty two percent learned that the order of preference for vegetables is fresh, frozen, and then canned.

When asked if they enjoyed taste testing the foods on the tour, 92% said yes. New foods were tasted by 68% of the participants. Most participants had not tasted edamame, dried fruit, sun-dried tomatoes, chick peas, artichoke, kefir/yogurt, or a yogurt smoothie. When asked to name the best part of the store tour participants provided more than one answer (n=154); 32% said learning from the interns, 20% said taste testing/tasting something new and 14% said learning how to cook/prepare in a healthier manner for nutrition benefits. Seventeen percent of participants reported learning how to read and understand a food label was the best part of the tour, while other responses were: "seeing the store in a new light”, "sharing ideas with other participants” and "all of it was great”.

Discussion

The participants in the store tours enjoyed learning from the interns and sharing information with each other, perhaps because the grocery store is a non-threatening learning environment. Participants were encouraged to ask questions on the spot about concepts which they didn't understand, such as which fats are healthiest. Store tour participants reported increased awareness of a variety of fruits and vegetables, how to select ripe ones, their importance in a healthy diet, and how to prepare them for consumption. These findings support the findings of the WIC study in which survey respondents indicated that they learned the importance of eating a variety of fruits and vegetables and that they and their families would increase their fruit and vegetable consumption, as 88% of our participants planned to do [5]. Similarly, the FOOD cents (low socio-economic) adult nutrition education program in Western Australia aimed to provide knowledge, skills and motivation to purchase nutrient dense foods on a budget for take-out over the past 20 years [8]. Smith and Jones performed a randomized study to examine the efficiency of the Expanded Food and Nutrition Education Program for low-income families [9]. Individuals that were part of this study were either assigned to immediate education or delayed education. During the first eight weeks, participants with immediate education received intervention, but the delayed education participants did not receive any intervention. Results showed that both the immediate and delayed education control groups improved behavior during their pre- and post-education. The current study supports the results of the WIC study and the FOOD cents study and the notion that "cues to action” (outside influences such as education) does bring about behavior change in low income populations.

Conclusion

The store tours given by interns, in this study, proved to be an effective way to teach the public how to shop and cook in a manner which should lead to better overall health. Providing nutrition education in a familiar, relaxed environment may be a better way of teaching lower income, minority populations, as opposed to teaching in a more formal setting, such as a clinic or physicians' office. Research supports that proper nutrition education does lead to behavior changes and thus may decrease the incidence of obesity, diabetes and hypertension in Memphis.

Funding

This project was funded by: The Better Produce for Health Foundation, Office of Minority Health and Disparities Elimination, Division of Health Disparities Tennessee Department of Health, Kroger stores of Memphis and the AARP Fresh Savings Program.

Authors Contribution

Williams Hooker developed the idea for the program. In addition, Dr Williams Hooker provided the oversight, conducted the analysis, and wrote the manuscript. Ms Ralston and Abounassif implemented the program, organized the tours and tour leaders, and contributed to the manuscript.

To Know More About Current Research in Diabetes & Obesity

Journal Please click on:

https://juniperpublishers.com/crdoj/index.php

To Know More About Open Access Journals Please click on: https://juniperpublishers.com/index.php

Comments

Post a Comment