Can Patients with Diabetes Detect their own Eating Disorder? The Need for A Better Understanding of Eating Pathology in Diabetes_Juniper Publishers

Authored by Annie Aimé

Abstract

Some authors have suggested that patients with

diabetes may hardly detect a co-morbid eating disorders. Unfortunately,

not doing so can negatively impact treatment and lead to several

unwanted medical complications and psychological problems. Moreover,

when a co-morbid eating disorder in a patient with diabetes is not

treated, it tends to be recurrent and persistent over time. This study

aims to compare patient's own report of eating problems to a diagnosis

established with the Eating Disorders Examination Questionnaire-6. A

total of 624 patients with diabetes (type 1 diabetes=137; type 2

diabetes=487) participated to an online survey. The results provide

support to the idea that people with diabetes may not adequately

evaluate whether they have a co-morbid ED or not. While many

participants reported eating problems that did not meet an ED diagnosis,

others thought they had no eating problems but their self-reported

symptoms met the criteria for an ED diagnosis. People with type 2

diabetes were more likely to report eating problems when there was no ED

diagnosis and people with type 1 diabetes were more at risk of denying

eating problems when they presented symptoms associated with an ED.

These results must be understood in light of the treatment

particularities of each type of diabetes: weight management is strongly

recommended in people with type 2 diabetes and monitoring of eating is

considered essential for those with type 1 diabetes. These patients'

difficulty to detect a co-morbid ED should be taken seriously given that

it may considerably impair their diabetes management.

Abbreviations: ED: Eating Disorders; PWD: Patients With Diabetes; T1D: Type 1 Diabetes; T2D: Type 2 Diabetes

Introduction

Recent research suggests that health professionals

might find difficult to detect eating disorders (ED) among patients with

diabetes (PWD) [1]. Moreover, the clinician's diagnosis impression may differ from the patients' own perception of their eating pathology [2].

In fact, according to Allan (2015), patients with type 1 diabetes’

(T1D) definition and conception of disordered eating behaviours doesn't

correspond to the psychiatric nosography suggested in the Diagnostically

and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders [3].

More precisely, T1D patients who believe they have an eating disorder

(ED) do not necessarily present a symptomatology that meets the

diagnosis criteria of specific eating disorders such as anorexia,

bulimia, or binge eating disorder [2].

For those who receive such a diagnosis, bulimia, binge eating disorder

and ED not otherwise specified seems to be the most prevalent diagnosis [4].

However, T1D patients themselves do not feel they have bulimia since

they do not consider insulin omission as a compensatory behaviour

associated to ED. To qualify their eating pathology, they instead tend

to refer to a non-classified eating pathology called "diabulimia" [2].

This implies that the detection of ED in T1D patients is problematic

and often doesn't match the ED they are diagnosed with. Such detection

problem and lack of recognition can lead to an inadequate management and

treatment of eating disorders symptoms in PWD. By not seeking and

receiving treatment for an ED, they expose themselves to deleterious

medical (e.g. bad glycemic control [5], elevated BMI [4,6] higher risk of retinopathy [7], nephropathy [8], neuropathy [6], cardiovascular problem [6], ketoacidosis [6]) and psychological (e.g. higher anxious [9] and depressive [10,11], symptoms, lower self-esteem [12] and self-directiveness [5], more as wishful thinking and self-blame [13], and perfectionism trait [8])

consequences. Furthermore, the impact on diabetic treatment can be long

lasting as eating disorders tend to be recurrent and persistent over

time [14]. Although up to 40% of patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D) report eating problems [15],

no study to our knowledge has examined the detection of ED among these

patients, thus leaving unanswered the question as to whether T2D

patients experience the same difficulties as T1D patients to detect and

recognize a co-morbid ED. This study aims at assessing ED in patients

with both types of diabetes and at comparing their own report of eating

problems to a diagnosis established with a valid measure of ED. A total

of 624 participants diagnosed with diabetes and aged 17 to 84 years old

were recruited to participate in a larger study focusing on the French

validation of the Diabetes Eating Problem Survey-Revised Gagnon et al. [16]

for a more detailed description of the study sample and procedure).

Among the participants, 137 individuals stated that they had a T1D and

487 declared having a T2D. Their self-reported body mass index (BMI=

kg/m2) [17]

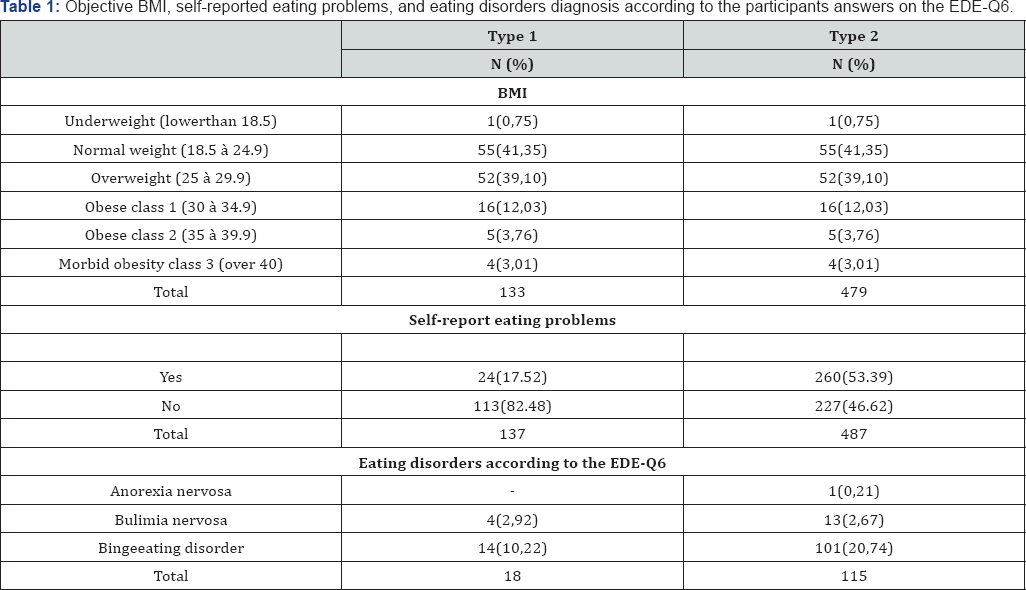

distribution is as follows: 1% of people with T1D were underweight, 41%

were of normal weight, 39% were overweight and 19% were obese (Table 1).

In people with T2D, none were underweight, 14% were of normal weight,

27% were overweight and 58% were obese. Participants were asked if they

considered having eating problems. They also filled in the diagnosis

items of the Eating Disorders Examination Questionnaire-6 (EDEQ-6) [18],

which is frequently used to assess the presence and frequency of core

eating behaviours involved in the diagnosis of ED (e.g. binge eating,

fasting, vomiting, exercising excessively, taking laxatives and

diuretics) as per the DSM-5 criteria [3].

As can be seen in Table 1

45.52% of the participants reported that they had eating problems:

respectively, 17.52% of people with T1D and 53.39% of people with T2D

reported such problems. In contrast, the participants' answers on the

EDE-Q6 suggest that 13% of people with T1D and 24% of people with T2D

had an ED. More precisely, according to the EDE-Q6, 87% of people with

T1D did not have an ED, 10% had BED, 3% had bulimia, and none had

anorexia nervosa. In people with T2D it was observed that 76% did not

have and ED, 21% had BED, 3% bulimia and 0,2% anorexia nervosa. Among

the participants who considered having eating problems, the proportion

of those who could not be diagnosed with an ED according to the EDE-Q6

was higher than the one of those who met the criteria for an ED. As

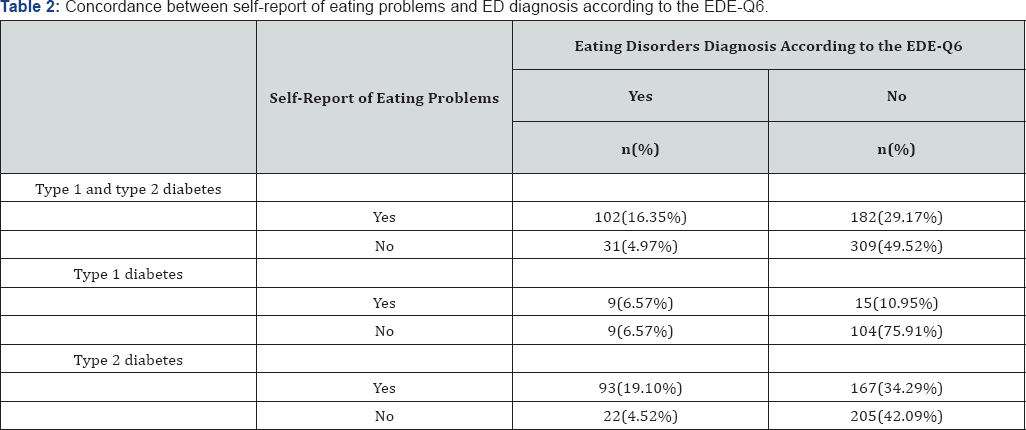

found in Table 2,

this was found in both types of diabetes. However, T2D patients were

more likely than T1D patients to report eating problems that did not

encounter ED diagnosis criteria (χ2(1) = 40.291, p <.001). T1D

patients who met ED diagnosis criteria were for their part significantly

more likely than T2D patients to deny having any eating problem (χ2(1) =

8.297, p < .05). In fact, people with T2D were 5.82 times more

likely than people with T1D to think they had eating problems while they

did not have an ED diagnosis and T1D patients were 4.23 times more at

risk of not reporting eating problems when they did in fact met the

diagnosis criteria for ED according to the EDE-Q6.

Conclusion

Results from this study reveal that close to half of

the PWD confide in having eating problems. However, for the majority of

them, the DSM-5 criteria for an ED are not met. The most frequent ED

diagnosis that was found in both T1D and T2D patients is binge-eating

disorder, followed by bulimia nervosa. Anorexia nervosa was found in

only one T1D participant. Interestingly, many participants believed they

had eating problems but a closer evaluation, based on their

self-reported symptomatology and the DSM-5 criteria, did not indicate

so. This is especially true for T2Dparticipants, with more than a third

of them reporting eating problems that did not seem to be severe enough

to meet ED diagnosis criteria. On the contrary, a small proportion of

the participants did not report any eating problems while their

responses to the diagnosis items of the EDE-Q6 suggest they have an ED.

This tendency to under-report eating problems was more likely to be

observed in T1D then T2D participants. Taken together, these findings

provide further support to the suggestion of Allan [2], who advances that detecting and recognizing a co- morbid ED, can be difficult for PWD.

In people with T2D, the tendency to report eating

problems in the absence of an ED could be partly explained by a higher

body mass index. In fact, over three quarter of the T2D patients were

either overweight or obese. This weight condition implies that they are

frequently reminded about the necessity to pay close attention to their

eating in order to lose weight [19].The

therapeutic approach in the context of diabetes management, especially

for those with T2D, focuses on eating control, weight management [19], weight measurement [20] and a loss of 5% to 7% of the actual weight [21].

In this context, diabetes patients can understand that they have an

eating problem that need to be treated. Additionally, as their feeling

of satiety might be altered by their diabetic medication [22]

losing weight can be quite a challenge and, when realizing they are

unable to do so, they may further believe they have eating issues

resembling to those found in ED. Thus, T2D patients may confound weight

management problems with eating problems and some psycho education about

ED could be beneficial for them in order to better understand the

symptoms of ED and better evaluate their likelihood of really having an

ED. On the contrary, approximately 5% of PWD don't think they have

eating problems while the EDE- Q6suggest they have one. This was

significantly more likely to be observed in T1D patients, which is in

line with Allan’s results [2]. Yet, in Allan's study [2]

a much higher proportion (38.8%) of people with T1D thought they had an

ED diagnosis while they did not have one. This difference in proportion

between both studies might be explained by the formulation of the

question that was asked in the current study: this question focused on

the participants’ perception of having eating problems and not precisely

on whether they believed they had an ED diagnosis. Also, participants

in Allan's [2]

study were recruited through a registered charity for PWD and ED -

Diabetics with Eating Disorders (DWED) -while the participants in the

current study were recruited in a registered charity for PWD

only-Diabetes Quebec. This implies that participants in Allan’s study [2] were already concerned with having an ED, which was not the case in this study. Notwithstanding these differences, Allan's [2]

results and the one obtained in the current study are alarming as they

imply that diabetes treatment management can be impaired by the absence

of ED acknowledgement. If PWD are unaware of in deny of having an ED,

they are strongly at risk of developing harmful and even fatal medical

complications and to endure long lasting and persistent eating problems [14].

Based on this study results, it seems that providing

PWD with information about EDs and about the fact that the eating

restrictions inherent to diabetic management can lead to ED appears very

relevant. In fact, not only PWD but also health professionals working

with them need to develop a more thorough understanding of how eating

problems and disorders are experienced by PWD and of their impact on

diabetes management. Standard guidelines about ED’s definition and

assessment in the context of diabetes could thus be beneficial for

clinical practice. As such, a more systematic evaluation and monitoring

of eating habits and symptoms seems important given that PWD are not

able to detect themselves whether or not they have an ED. Although the

EDE-Q6 can't be used alone for establishing and ED diagnosis, it shows

good agreement with the diagnosis interview [21]

and thus could represent a good tool to assess eating pathology in PWD.

Along with it, other measures such as the Diabetes Eating Problem

Survey-Revised (DEPS-R) [23] could be considered.

To Know More About Current Research in Diabetes & Obesity

Journal Please click on:

https://juniperpublishers.com/crdoj/index.php

https://juniperpublishers.com/crdoj/index.php

There are some natural remedies that can be used in the prevention and eliminate diabetes totally. However, the single most important aspect of a diabetes control plan is adopting a wholesome life style Inner Peace, Nutritious and Healthy Diet, and Regular Physical Exercise. A state of inner peace and self-contentment is essential to enjoying a good physical health and over all well-being. The inner peace and self contentment is a just a state of mind.People with diabetes diseases often use complementary and alternative medicine. I diagnosed diabetes in 2010. Was at work feeling unusually tired and sleepy. I borrowed a cyclometer from a co-worker and tested at 760. Went immediately to my doctor and he gave me prescription like: Insulin ,Sulfonamides,Thiazolidinediones but Could not get the cure rather to reduce the pain but brink back the pain again. i found a woman testimony name Comfort online how Dr Akhigbe cure her HIV and I also contacted the doctor and after I took his medication as instructed, I am now completely free from diabetes by doctor Akhigbe herbal medicine.So diabetes patients reading this testimony to contact his email drrealakhigbe@gmail.com or his Number +2348142454860 He also use his herbal herbs to diseases like:SPIDER BITE, SCHIZOPHRENIA, LUPUS,EXTERNAL INFECTION, COMMON COLD, JOINT PAIN, EPILEPSY,STROKE,TUBERCULOSIS ,STOMACH DISEASE. ECZEMA, PROGENITOR, EATING DISORDER, LOWER RESPIRATORY INFECTION, DIABETICS,HERPES,HIV/AIDS, ;ALS, CANCER , MENINGITIS,HEPATITIS A AND B,ASTHMA, HEART DISEASE, CHRONIC DISEASE. NAUSEA VOMITING OR DIARRHEA,KIDNEY DISEASE. HEARING LOSSDr Akhigbe is a good man and he heal any body that come to him. here is email drrealakhigbe@gmail.com and his Number +2349010754824

ReplyDelete