Health Differences across the Three Obesity Classes: Evidence from the 2012 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System_Juniper Publishers

Authored by Ari Mwachofi

Abstract

Obesity increases the burden of disease, decreases

the quality of life and life expectancy, and contributes over $200

billion annually to US health expenditures. Although there are three

distinct obesity classes, most studies lump them together and examine

obesity as one condition. Analysis of health effects of the three

obesity classes could provide leads to more targeted and insightful

interventions.

Objectives: The study questions are: Are there

health differences in self-assessed health across the three obesity

classes? Are there differences in prevalence of diagnosed chronic health

conditions in these obesity classes?

Method: We address the study questions through

analysis of data from the 2012 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance

System (BRFSS) of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

(CDC).We define six body-weight groups: BMI≤18.5 as underweight; healthy

body weight as18.5≤BMI<25; overweight as 25<BMI<30; Classl

obeseas 30≤ BMI <35; Class2 obese as 35≤BMI<40; and Class3 obese

as 40≤ BMI. We conduct χ2 and t-tests of differences in

self-assessed health status and prevalence of diagnosed chronic health

conditions in the three obesity classes. Applying a health production

framework from health economics, and using overweight and healthy

body-weight as the control group, we conduct multivariate analysis of

the effects of obesity on self-assessed general and physical health.

Result: There are significant (p<0.000)

differences in self-assessed health status, and in prevalence of

diagnosed chronic health conditions across these obesity classes. The

higher the obesity class the poorer the health. Class 3 has the largest

negative effect on the likelihood of good general and physical health.

Conclusion: Health differences across obesity

classes suggest the need to examine obesity in greater detail. Rather

than addressing obesity as a single problem, it might be more helpful to

examine levels of obesity and to tailor interventions to specific

body-weight classes.

Introduction

Obesity is one of the most costly public health problems in the world. In 2008, an estimated 502 million adults were obese [1]. On average in the US, obese individuals die 9.44 years earlier than those not obese [2], which equals more than 125 million years of potential life lost due to obesity [3]. An estimated 111,909 extra deaths occur among obese people compared to deaths among individuals with healthy body weights [4]. Between 2011and 2012, 78.6 million people in the United States (34.9% of adults) were obese [5]. Annually in the US, 3.4 million quality-adjusted life years are lost to obese women and 1.94 million to obese men [6]. Obesity not only has serious physical health implications, but also has serious mental health consequences [7,8].

Estimates of obesity-attributable excess medical expenditures amount to

$147 billion annually while productivity losses amount to $66 billion [9].

Obesity exacerbates over twenty major chronic health conditions [10].

It is both a primary and secondary risk factor for coronary heart

disease and is positively correlated with the prevalence and severity [11-16]. Some evidence suggests that obesity affects strokes [17-19] and asthma is a well-documented co morbidity for obesity [20-23]. People with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) have higher prevalence of obesity and

obesity in COPD patients is associated with significantly more severe activity limitations and increased health care utilization

[24]

. However, a closer examination of COPD conditions shows that patients

with chronic bronchitis are more likely to be obese while those with

emphysema are more likely to be underweight

[25] .

Obesity is related to numerous cancers. Esophageal

adenocarcinoma is aggravated by obesity through reflux esophagi is and

chronic irritation [26]. Obesity-related inflammation leads to multiple myeloma and Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma [27], and might result in chronic kidney disease [28]. Obesity is also linked to renal cancer [29], to colon, pancreatic and liver cancers [30,31] and to gallbladder cancer [32]. In women, obesity is linked to endometrial and pre- and postmenopausal breast cancers [33]. Other obesity-related cancers include thyroid, rectal, leukemia, prostate and malignant melanoma [34]. Among individuals diagnosed with cancer, those who are obese have decreased survivorship [35].

Obesity research mostly combines all obesity groups

together and focuses on prevalence, but not on obesity variations and

their differential effects on health [36-38].

In consideration of obesity heterogeneity and the scope of management

options, three classes are defined as Class 1including BMI from 30 to

less than 35; Class 2 also known as severe obesity, including BMI of 35

to less than 40; and Class 3also known as morbid obesity, including BMI

that is equal to or greater than 40 [39].

Study Objectives

The main study question is: Are there health

differences across the three obesity classes? Related questions are: Are

there differences in prevalence of chronic health conditions in these

obesity classes? Relative to individuals with healthy body weight, what

is the health status of individuals in the three obesity classes?

Study Methods

Study model

The study applies a household health production

framework from health economics, which posits that the household

produces health using household, individual and environmental inputs [39]. Some health production inputs (e.g. meals, shelter) are produced by the household. The basic model used in previous studies [40-42], can be represented by the following health production function:

Hi= f( Ii,E,)............. (1)

Where: the subscript i denotes the individual as the

unit of analysis; H is a vector depicting health output; I is a set of

individual and household variables (inputs) and E represents

environmental inputs. Researchers have applied this framework in studies

of various health-related phenomena such as effects of prenatal care on

birth weights [43]. Household production and demand for health inputs and their effects on birth weights [44], Effects of childhood and education on health [45], the impact of maternal smoking on child neuro development [46] and the relationship between household production, fertility and child mortality [47].

Within the health production framework, obesity

Classes 1, 2 and 3 are individual variable inputs in health production.

These classes might also be representative of health behavior (such as

diet and exercise) or descriptive of health capital stock [40].

Based on the household health production process represented by

equation 1 above the econometric model used in multivariate analysis of

general health (GH), and physical health (PH) has the following two

equations:

GHi= f( Di,Si Bi,Hi Ei).............. (2)

PHi= f( Di,Si Bi,Hi Ei)............. (3)

Where: D represents demographic factors; S is

socioeconomic status (SES); B is health behaviors; H is health capital

stock, E are environmental factors such as access to care. These

equations were utilized in multivariate analysis examining the effects

of the three obesity classes on health.

Health is measured as

- Self-assessed general health status

- Self-assessed physical health status, and

- Number of poor health days experienced within a 30- day period.

Data source and study sariables

The study data are from the 2012 Behavioral Risk

Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) survey. BRFSS is an annual nationwide

telephone survey of non-institutionalized adults. The survey is

conducted by the CDC in collaboration with health departments in all

states [48].

The survey is based on a multistage cluster design that uses

random-digit dialing to select samples that are representative of the US

population.

Dependent variables: The 2012 BRFSS survey had

questions about individual self-assessed general health (GH) status:

Would you say that in general your health is 1. Excellent, 2.Very good,

3. Good, 4. Fair, or 5. Poor? Responses to this question were coded one

(1) for excellent, very good or good health and zero (0) for fair or

poor health. Other BRFSS questions quantify poor health experiences in

number of days of poor health within a 30-day period: Now thinking about

your physical health, which includes physical illness and injury, for

how many days during the past 30 days was your physical health not good?

Responses to these questions provided quantitative measures of the

individuals' experiences of poor health.

Independent variables: Data about BMI, the

variable of interest, were derived from responses to two BRFSS

questions: About how much do you weigh without shoes? About how tall

are you without shoes? Responses to these questions were used to

calculate respondents' body mass index (BMI), which was then coded into

six weight classes: BMI<18.5 is underweight; 18.5≤BMI<25 is

healthy weight; 25≤BMI<30 is overweight; 30≤BMI< 35 is Class1

obese; 35≤BMI< 40 is Class 2 and BMI≥40is Class 3 obese.

Other questions gathered data about demographics

(age, ethnicity, sex/gender, race, marital and veteran status) and

socioeconomic status (SES) such as income, employment, home-ownership,

educational levels and access to personal cell-phones. Other questions

were used as surrogate measures of household climate. These include

number of dependent children, if the household is female headed with no

adult males or if it is male headed with no adult females. Measures of

individual health behavior include tobacco and alcohol use, physical

exercise, the use of seatbelts in automobiles, getting vaccinations, and

health screenings such as HIV-tests. BRFSS also provided data about

access to care and health capital stock. Access to care was measured

using three variables: having health insurance and personal doctors and

inability to access care due to high costs of care. Individual stock of

health capital was measured as disability status and diagnosed chronic

health conditions. The two measures of disability used responses to

BRFSS questions: Are you limited in any way in any activities because of

physical, mental, or emotional problems? Do you now have any health

problem that requires you to use special equipment, such as a cane, a

wheelchair, a special bed, or a special telephone? Responses to these

questions were coded one (1) for "yes" and zero (0) for "no." Data about

diagnosed chronic health conditions were derived from responses to

BRFSS survey question: Has a doctor, nurse, or other health professional

EVER told you that you had any of the following: heart attack also

called a myocardial infarction, angina or coronary heart disease,

stroke, asthma, skin cancer, other types of cancer, chronic

obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), arthritis, depressive disorder,

kidney disease, trouble seeing, diabetes? Responses to these questions

were coded one (1) for "yes" and zero (0) for "no."It is

important to note that BRFSS defines arthritis to include rheumatoid

arthritis, gout, lupus, or fibromyalgia and COPD to include emphysema or

chronic bronchitis.

Analysis Methods

We use dt- and x2 tests for statistical significance

of health differences across the obesity classes. We used x2 testsfor

categorical variables and t-tests on differences in the number of days

of poor health within a 30-day period. We conducted three sets of tests:

differences betweenClasses1 and 2, Classes 1 and 3 and differences

between class 2 and 3.

Multivariate analysis estimated the likelihood of

good health as represented in equations 2 and 3above, and enabled the

study to measure the effects of the three obesity classes (relative to

the control group) while controlling for other health production

factors. In estimating the differential effects of the three obesity

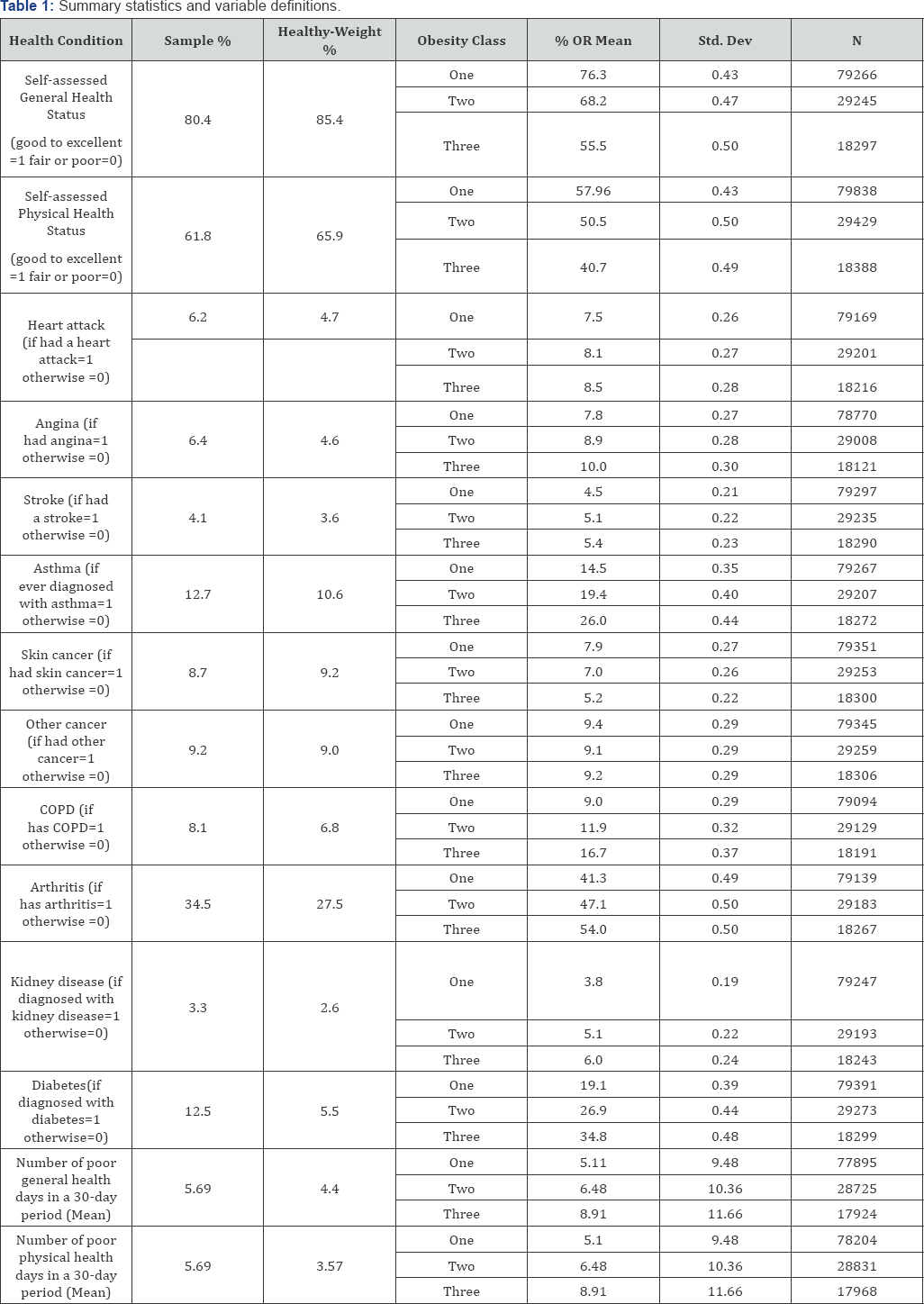

classes, the study used normal and overweight groups as the controls. Table 1

displays summary statistics of the study sample, which is drawn from

all states in the US. It includes health condition, obesity class and

the variable definitions applied in the study. The obesity class with

the largest number of respondents is Class 1 while Class 2 had the

smallest number. As expected, individuals who are obese have worse

health than those with healthy body weights. The proportion of

individuals with healthy body weights who were diagnosed with chronic

health conditions is much lower than proportions in the three obese

classes. Those who are obese also experience more days of poor health

than those with healthy body weights. They also have lower proportions

with self-assessed good or excellent health status.

These data also show that the higher the obesity

class, the poorer the health. For example individuals with obesity Class

1 have better general health (greater percentage with excellent to good

health and fewer number of poor health days) than those in the other

two classes. Individuals who are Class 2 obese have slightly better

health than the Class 3 obese. This is also true for diagnosis of all

chronic conditions except for cancer. The trend for skin and other

cancer diagnosis is opposite. Class 1 obese has greater proportions

diagnosed with these two conditions than Class 2 or Class 3 obese but

lower proportions than individuals with healthy body weights.

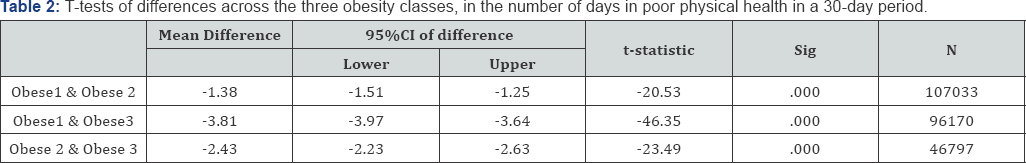

Results of t-tests of differences in number of days

that respondents experienced poor health within a 30-day period are

displayed in Table 2.

The higher the obesity class, the greater the number of poor health

days. Individuals with Class 1 obesity experience 1.38 days less of poor

physical health than individuals with Class 2 and 3.81 days less than

those with Class 3. Class 1 individuals also experience 1.08 days less

of poor mental health than those with Class 2 and 2.68 days less than

those with Class 3 obesity. Furthermore, individuals with Class 2

obesity have fewer days of poor physical (2.43 days less) and mental

health (1.6 days less) than individuals with Class 3 obesity. All the

differences are statistically significant (p<0.000).

Differences in self-assessed health status and in diagnosed chronic conditions

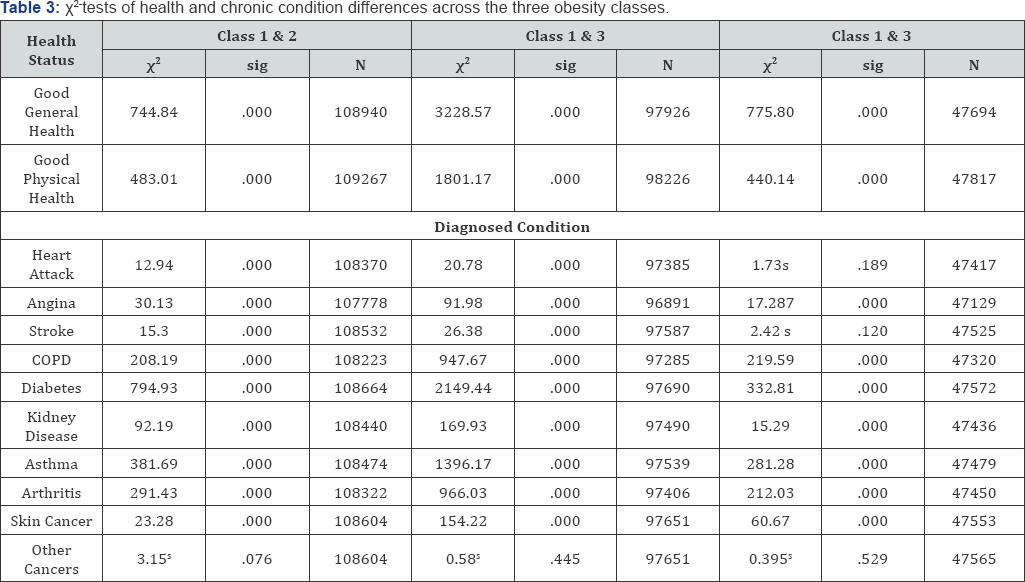

Table 3 displays results of χ2-test

of differences in selfassessed general and physical health and

diagnosed chronic conditions. Similar to differences in number of days

of poor health, individuals with Class1 obesity have better

self-assessed general health and lower proportions diagnosed chronic

conditions than those in the higher obesity classes.

As indicated by the χ2 statistics, all

differences between Classes 1 and 2 obese are statistically significant

except for proportions diagnosed with other cancers. The differences in

this diagnosis are small and statistically insignificant. The greatest

and most significant differences between Classes 1 and

2 is self-assessed general and physical health and in proportions

diagnosed with diabetes, asthma, arthritis and COPD.

As noted earlier, the greatest differences are

between individuals with obesity Classes 1 and 3. All differences

between these two classes are statistically significant except for

proportions diagnosed with other cancers. This difference is small and

statistically insignificant. The most significant differences between

Classes 1 and 3 are in self-assessed general and physical health and in

proportions diagnosed with diabetes,asthma, arthritis and COPD.

Differences between Classes 2 and 3 are less pronounced and some are

statistically insignificant. These include differences in proportions

diagnosed with heart attack, stroke, and other cancers. The most

pronounced differences between Classes 2 and 3 obese are in

self-assessed general and physical health and the proportions diagnosed

with diabetes, asthma, COPD and arthritis.

asthma, arthritis and COPD. Differences between Classes 2 and 3 are less

pronounced and some are statistically insignificant. These include

differences in proportions diagnosed with heart attack, stroke, and

other cancers. The most pronounced differences between Classes 2 and 3

obese are in self-assessed general and physical health and the

proportions diagnosed with diabetes, asthma, COPD and arthritis.

Multivariate analysis result

The control group for this analysis was individuals

with BMI ranging between 18.5 and less than 25 (18.5 ≥BMI < 25). This

BMI range includes individuals with healthy weights and the over-weight

group. This analysis included the underweight class (BMI<18.5) as an

explanatory variable. Other explanatory variables are demographics

(gender age, ethnicity), household climate, weight/obesity class,

socioeconomic status, individual health behavior (smoking, drinking,

physical exercise, seat-belt use, taking necessary tests/screenings, and

taking necessary vaccination), access to care and health capital stock

measured in terms of diagnosed chronic health conditions. Multivariate

analysis results appear in Tables 4 & 5.

Likelihood of good general health Table 4

displays results of estimates of the likelihood of good general health

and the effects of three obesity classes on the likelihood of good

general health. Relative to the control group (normal- and overweight),

all obesity levels have a negative and statistically significant (P≤

0. 000) effect on the likelihood of good general health. The Wald

statistics of the three obesity classes indicate that the Class 3

(BMI≥40) has the most significant negative effects while Class 1 has the

lowest effects. The coefficients are: -.079 for Class 1, -.258 for

Class 2 and-.469 for Class 3 obesity. These numbers suggest that Class 3

obesity has almost six times greater negative effect on the likelihood

of good general health than Class 1 and that Class 2 has more than three

times greater effect than Class

1. These numbers indicate that the greater the obesity level, the

greater the negative effect on the likelihood of good general health.

Other statistically significant negative predictors

of the likelihood good general health include being Latino/a,

underweight (BMI<18.5), unemployed, barriers to accessing health care

and having poor health capital (i.e. having chronic health conditions).

However, being female or young significantly and positively affect the

likelihood of good general health. The same is true about being in a

household with no adult males and having dependent children.

Furthermore, the results indicate that some measure of good health

behavior (not smoking, engaging in physical exercise and wearing seat

belts) positively and significantly affects the likelihood of good

general health. Conversely some indicators of health behaviors

(HIV-testing, pneumonia shots) show negative effects.

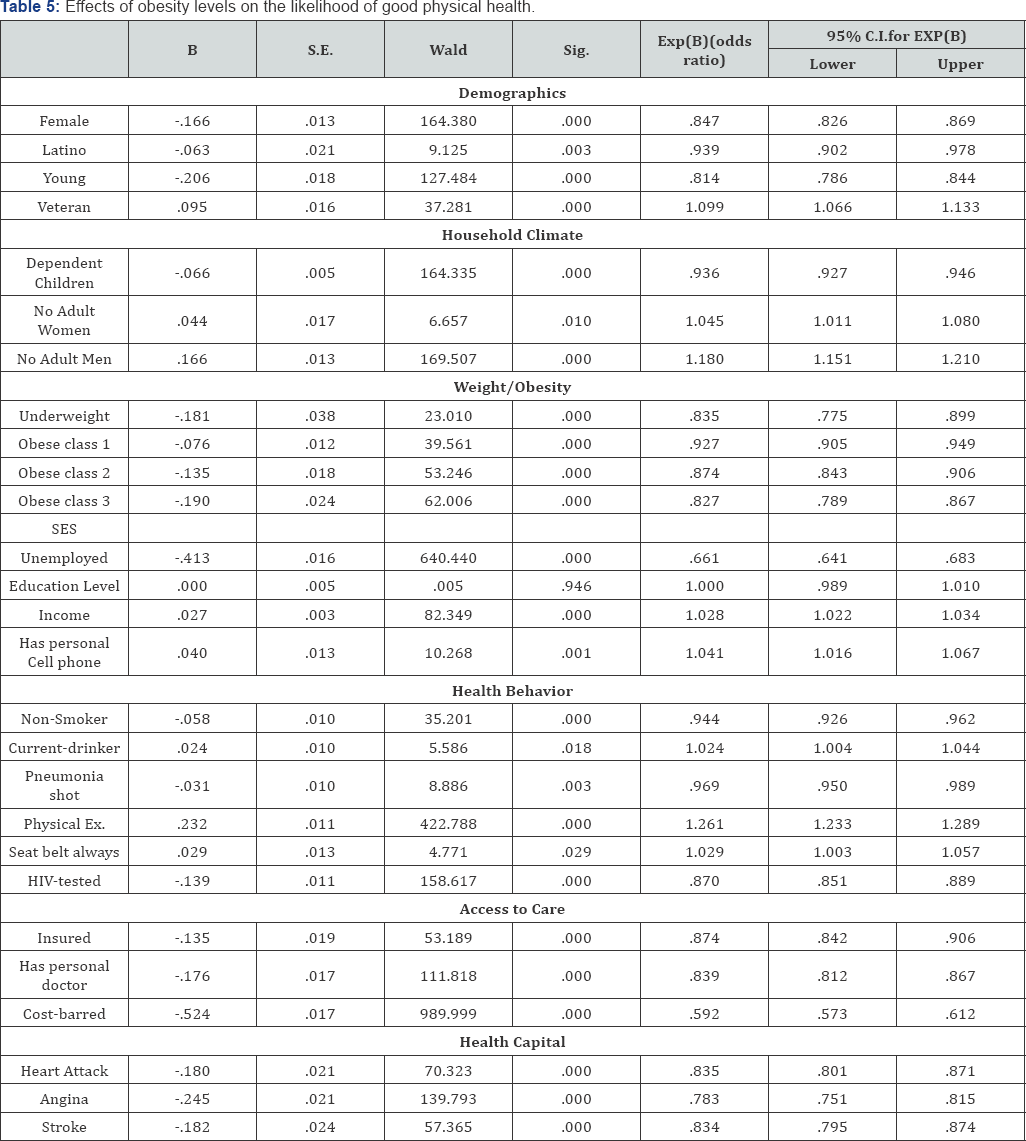

The likelihood of good physical health Table 5

Physical health analysis results is similar to the general health

results. They indicate that all three obesity classes negatively and

significantly (P≤ 0.000) affect the likelihood of good physical health.

The coefficients also indicate that the higher the obesity class, the

greater the effects. The Wald statistics suggest that the higher the

obesity class, the more significant the effects on the likelihood of

good physical health. Other statistically significant negative

predictors of the likelihood good physical health include being female,

Latino/a, young and underweight (BMI<18.5), unemployed, having

dependent children, having barriers to accessing health care and having

poor health capital stock (i.e. having chronic health conditions).

Discussion

The study results indicate significant health

differences across the three obesity classes. The higher the obesity

class, the lower the likelihood of good self-assessed general or

physical health and the more the number of days the individuals

experienced poor health. The higher the obesity class, the greater the

proportions diagnosed with chronic health conditions except for skin

cancer where the trend is opposite the higher the obesity class, the

lower the proportions diagnosed with skin cancer. A possible explanation

for this outcome could be that people with heavier weights are less

likely to sunbathe than people with less bodyweight. With current

emphasis and attention to evidence-based care and interventions, it is

necessary to recognize that there are variations in obesity levels and

in their effects on health and quality of life. It is important to

gather detailed information about the different obesity classes and the

different effects they have on health. Such information will provide

means of creating more targeted interventions and treatments. Armed with

detailed information and evidence about the different obesity levels,

practitioners and policy makers can avoid painting obesity with a broad

brush, which might create interventions that might not work for all

obesity levels. For effective evidence-based interventions, it is

necessary to decipher the varying effects of obesity on health

conditions and to find out which conditions are affected by what obesity

levels and how.

These findings indicate that the three obesity levels

have different impacts on health. Individuals with Class 3 obesity

experience about 4 days more of poor physical health, 3 days more of

poor mental and general health per month that those with Class 1

obesity. The difference between Classes1 and 2 is about one day more

while between Classes 2 and 3 is about 2 days. Viewed in terms of

current US average hourly earnings of $25.25 [49],

4 days difference between obesity Classes 1 and

3 translates into $808 earned per month, or $9,696 per year- a

significant difference. These numbers suggest significant differences in

the impact of obesity classes on productivity.

Furthermore, after controlling for other factors that

affect health, including demographics, household climate, SES, health

behavior, access to care and individual health capital stock, relative

to individuals with normal weight or those slightly overweight, those in

the three obesity classes have lower likelihoods of experiencing good

physical or good general health. An examination of the likelihood of

good general health reveals that obesity Class 3 has close to six times

the negative effects of Class 1, while Class 2 has three times the

effects of Class 1. Obesity Class 3 has about two times the negative

effects of Class 2 on the likelihood of good general health. Similarly,

an examination of the likelihood of good physical health reveals that

obesity Class 3 has 2.5 times the negative effects of Class 1. Obesity

Class 2 has 1.8 times the negative effects of Class 1 on the likelihood

of good physical health.

Conclusion

Health effects of obesity vary by obesity class.

These findings are significant even after controlling for other factors

that affect health such as demographics, socioeconomic status, household

climate, individual health behavior, access to health care and

individual health capital stock. The effects of each obesity class are

different. The pattern of obesity effects on physical and general health

is different from the mental health. Given these differences and

current emphasis on evidence-based interventions and treatments, it is

important to examine obesity variations rather that viewing it as a

single health condition. The obesity levels might require more targeted

interventions rather than a single intervention for all three classes.

To Know More About Current Research in Diabetes & Obesity

Journal Please click on:

https://juniperpublishers.com/crdoj/index.php

https://juniperpublishers.com/crdoj/index.php

Comments

Post a Comment