Antidepressant Prescription Practices among Primary Health Care Providers for Patients with Diabetes Mellitus_Juniper Publishers

Authored byBartlett G

Abstract

Purpose: Depression is a common comorbidity in

people with diabetes that increases the risk of poor diabetes control

and diabetes- related complications. While treatment of depression is

expected to help, some antidepressants have been associated with

impaired glucose metabolism. Evidence is lacking in the scope of this

problem for people with diabetes. The objective of this study is to

describe the prescription of antidepressants for diabetic patients with a

focus on medications suspected to impair glucose control.

Methods: A cross-sectional study of electronic

medical record data from 115 primary care practices in the Canadian

Primary Care Sentinel Surveillance Network was conducted. Descriptive

statistics were used to describe the prescription of antidepressants for

people with diabetes between 2009 and 2014.

Results: From the sample, 17,258 diabetic

patients were prescribed at least one antidepressant (AD) between 2009

and 2014. In terms of pharmacological class, the greatest proportion of

people were prescribed selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (46.2%),

followed by serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (24.3%) and

tricyclic antidepressants (23.8%). The most frequently prescribed

medications were Citalopram (16.6%), Amitriptyline (16.2%), Venlafaxine

(15.7%), Trazodone (14.2%), Escitalopram (12.4%) and Bupropion (9.2%).

Almost half of diabetics were prescribed ADs potentially associated with

impaired glucose metabolism (SNRIs or TCAs).

Conclusion: The present study provides a

description of AD prescription in primary care for people with diabetes

by class and medication. The findings indicate that the issue of glucose

impairment has little impact on selection of ADs for people with

diabetes. Further research is needed to determine the health impact of

these practices.

Keywords: Diabetes; Antidepressants; Depression; Primary care; Electronic health records; Pharmacoepidemiology

Abbreviations:

AD: Antidepressant; ATC: Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical; CPCSSN:

Canadian Primary Care Sentinel Surveillance Network; COPD: Chronic

Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; EMR: Electronic Medical Records; MAOI:

Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitor Noradrenergic; NaSSA: Specific Serotonergic

Antidepressant; NDRI: Norepinephrine-dopamine Reuptake Inhibitors; SARI:

Serotonin Antagonist and Reuptake Inhibitor; SSRI: Selective Serotonin

Reuptake Inhibitor; SNRI: Serotonin-Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitor;

T1DM: Type 1 diabetes mellitus; T2DM: Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus; WHO:

World Health Organization

Introduction

Depression is a common comorbidity in people with

diabetes mellitus which increases the risk of macrovascular and

microvascular complications [1-3].

The relationship between depression and diabetes is bi-directional.

People with diabetes are more likely to suffer from depression compared

to those without diabetes [4] and depression is associated with poor glycemic control in people with diabetes [5,6].

Treatment of depression is expected to break this cycle, but recent

evidence suggests that some classes of antidepressants (AD) are

associated with impaired glucose metabolism, increasing the risk of poor

glycemic control [7,8].

Specifically, clinical trials suggest that Tricyclic antidepressants

and Serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors may be associated

with poor glucose control [8-10].

Given the risk ADs may pose, especially for people with diabetes,

knowledge about the prescription of ADs for people with diabetes is

needed.

At present, there is a lack of observational research describing the prescription frequency of ADs for people with diabetes [11]. In a recent cross-sectional study, Wong et al. [12] describe the prescription of ADs in a pan-Canadian primary care population with a history of depression [12];

however, AD prescription is grouped by pharmacological class. As ADs

within the same pharmacological class may differ in terms of their

impact on glucose metabolism [13],

information on the prescription of individual AD agents is needed. The

prescription frequency of individual ADs is reported for the province of

Quebec [14],

but it is unknown whether AD Whether AD prescription in a general

Canadian population or a smaller provincial study is the same as

prescription of ADs for people with diabetes. The purpose of this study,

therefore, is to describe the prescription of ADs for people with

diabetes, which particularly focus on medications that may impact blood

glucose control.

Methods

Methods Data source and study population

The present cross-sectional study was conducted using

primary care data extracted for public health surveillance and research

purposes by the Canadian Primary Care Sentinel Surveillance Network

(CPCSSN). At the time of the extraction, (September 30 2014), the CPCSSN

database comprised health records from 115 primary care practices in 7

Canadian provinces and 1 territory. The electronic medical records (EMR)

of 985,176 patients were extracted, anonymized, cleaned, coded and

centralized by the CPCSSN [15].

The present study sample comprises all adult (18 years of age and over)

patients (n=66,617) with diabetes in the CPCSSN database at the time of

extraction. From this sample, 5 annual cross-sections of diabetic

patients prescribed ADs between October 1, 2009 and September 30, 2014

(n=17,258) were generated. This was further reduced to the 2014

cross-section (n=10,152) to reflect current prescription practices.

Diabetes

Diabetes cases were identified using the validated

CPCSSN algorithm that detects cases using a combination of information

from patients' problem list, medication prescription records, laboratory

results and billing [16].

The diabetes case definition includes both type 1 diabetes (T1DM) and

type 2 diabetes (T2DM). The case definition for diabetes has a

sensitivity of 95.6 95% CI: 93.4-97.9 and a specificity of 97.1 95% CI

(96.3-97.9) [16]. The study sample comprises patients identified as having diabetes at the time of data extraction.

Depression

Cases of depression were identified using a validated

case detection algorithm developed by the CPCSSN which combines

information from patients' problem list, prescription records and

billing. The case definition for depression includes depressive, bipolar

and manic disorders. The algorithm detects lifetime depression-at least

one occurrence of one of the above mood disorders (hereafter "history

of depression"). The CPCSSN case definition for depression has a

sensitivity of 81.1 95% CI: (77.2-85.0) and a specificity of 94.8 95%

CI: (93.7-95.9) [16].

Antidepressants

Medications in the patient health records were

assigned World Health Organization (WHO) Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical

(ATC) codes. Medications classed as antidepressants (ATC N06A) by the

WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology [17]

were included. The pharmacological classes reported here are:

tricyclics (TCA); selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI);

serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRI); serotonin

antagonist reuptake inhibitors (SARI)- comprising only Trazodone;

monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOI); norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake

inhibitors (NDRI) and noradrenergic and specific serotonergic

antidepressants (NaSSA). ADs are classified according to the drug's

molecular structure and/or the way they interfere with the serotonergic

and norepinephrine neurotransmitter systems, rather than in terms of

their receptor affinity and mechanisms of action [13].

Therefore, the action of AD agents within the same pharmacological

class can differ greatly and their impact on glucose metabolism may be

distinct. AD prescription is therefore reported in terms of individual

medication as well as by pharmacological class.

Other variables of interest

Patients are characterized in terms of age, sex, body

mass index (BMI), concurrent health conditions, and diabetes medication

prescription. Age at the date of extraction was computed using

patients’ dates of birth. A median BMI was computed for each patient

using all BMI measures listed in their files. The median BMI was

selected as a more reliable value (less susceptible to outliers) than

the most recent measure or mean, given that a number of measures were

suspected to be in error (outside the expected range and/or computed

using weight in pounds rather than kilograms). Since BMI does not

generally change a great deal over time [18],

use of a fixed BMI measure is justifiable. The concurrent health

conditions reported consist of conditions for which validated case

definitions were developed by the CPCSSN: hypertension, depression,

osteoarthritis, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

Diabetes medication prescription was identified using ATC

classification. This information was categorically transformed to

approximate diabetes type and severity: insulin only (T1DM), oral

diabetes medications only (non-insulin-dependent T2DM), and both insulin

and oral diabetes medications (insulin-dependent T2DM).

Statistical analyses

The sample population is described using frequencies

and proportions, and means and standard deviations, as appropriate.

First, the characteristics of the sample of patients with diabetes and

prescribed ADs in 2014 (n=10,152), stratified by sex, are reported.

Second, AD prescription frequencies and proportions (by pharmacological

class and individual AD agent) for the 2014 cross-section, stratified by

sex and history of depression, are reported. Finally, as a sensitivity

analysis, the frequencies and proportions of AD prescriptions are

described through a 5-year comparison of annual cross-sections of

patients prescribed ADs between 2009 and 2014. Analyses were performed

using SAS version 9.4.

Ethics

The CPCSSN received ethics approval from the research

ethics boards of all host Universities for all participating networks

and from the Health Canada Research Ethics Boards. The present study

received ethics approval from the McGill University Faculty of Medicine

Institutional Research Board.

Results

Population characteristics

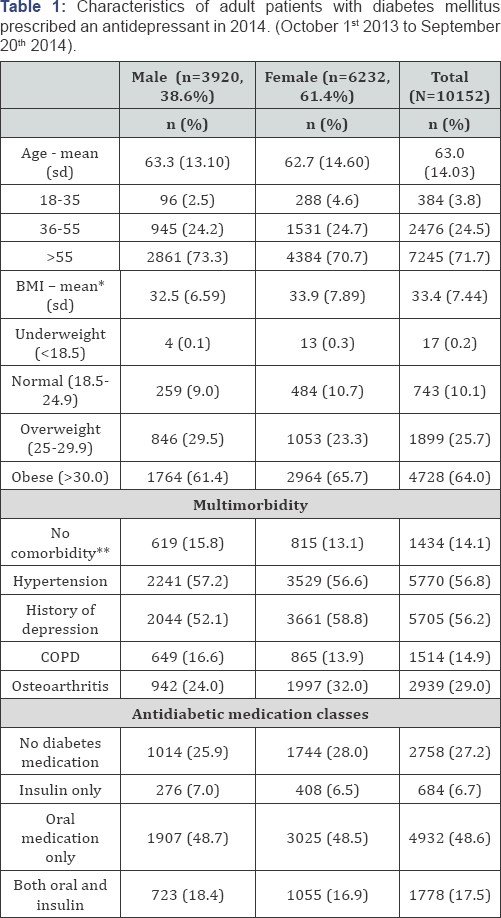

Table 1 provides

description of characteristics of diabetic patients prescribed ADs in

2014 (n=10,152), stratified by sex. This sample is described according

to age, BMI, presence of co-morbidities and anti-diabetic medication

prescription. In the cohort of diabetic patients prescribed ADs in 2014,

more of the patients were female than male. Among those with BMI

measurements (n=7, 387; 27.2% missing), almost all were overweight and

nearly two thirds were obese (BMI>30kg/ m2). History of

depression was identified in over half of the sample. With regard to

other comorbidities, hypertension was most frequent, followed by

osteoarthritis and COPD. Regarding prescription of anti-diabetic

medication, most were prescribed oral medications, followed by a

combination of oral medications and insulin, and less than 10% were

prescribed insulin alone. In over¼ of the diabetic patients, no

prescription of diabetes medications was identified.

*Group mean of individuals' median BMI values

**None of the conditions for which CPCSSN case definitions were developed

Characteristics of males and females in the sample

were generally comparable, with a few exceptions. Mean age and mean BMI

(group mean of the individuals’ median values) were comparable between

the sexes. Males were only slightly older than females, and slightly

more females were obese than males. Very slight differences in diabetes

medication prescription were observed, with more males than females

prescribed insulin (either alone or in combination with oral

medications).

Antidepressant prescription

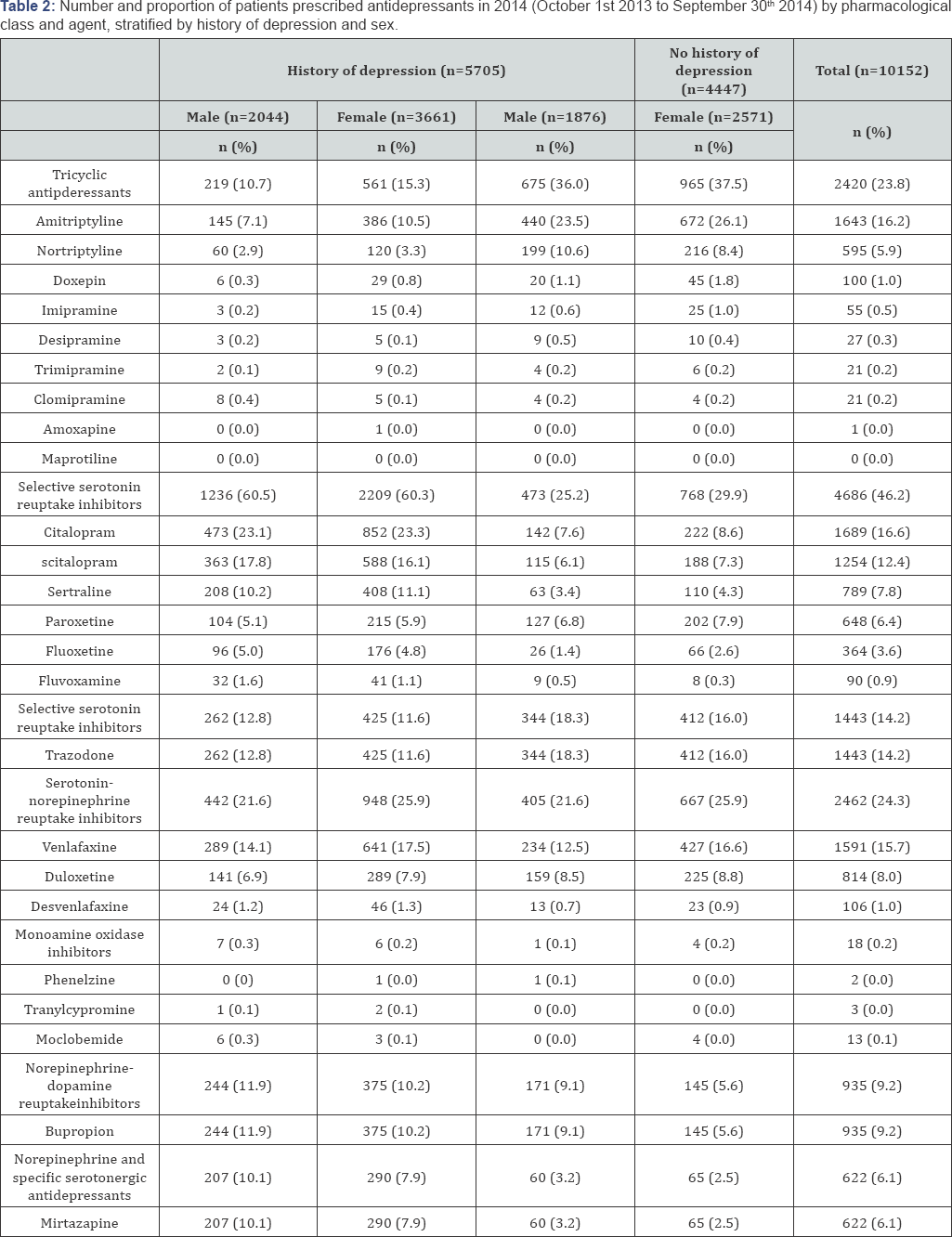

Table 2

presents the frequency and proportion of ADs prescribed for the 2014

cross-section of diabetic patients, in terms of pharmacological class

and individual medication, stratified by sex and history of depression.

The most frequently prescribed AD classes given to people with diabetes

were SSRI, followed by SNRI, TCA, SARI, NDRI, NaSSA and MAOI. A trend

was observed in which the prescription of certain ADs for patients with a

history of depression differed from those without. For diabetics with a

history of depression, the most commonly prescribed classes were SSRI,

followed by SNRI, TCA, SARI, NDRI and NaSSA. The most frequently

prescribed classes of AD given to diabetic patients without depression

were TCAs, followed by SSRIs, SNRIs, SARIs, NDRI and NaSSA.

The most frequently prescribed AD agents given to

diabetic patients with a history of depression were Citalopram,

Escitalopram, Venlafaxine, Trazodone, Bupropion, Amitriptyline and

Sertraline. For diabetic patients without a history of depression, the

most frequently prescribed ADs were Amitriptyline, Trazodone,

Venlafaxine, Nortriptyline, Duloxetine, Citalopram and Bupropion. In

people with diabetes and a history of depression, more females than

males were prescribed ADs in general. The proportion with which

individual ADs were prescribed were generally comparable between the

sexes, with a few exceptions. Amitriptyline and Venlafaxine were more

often prescribed for females than males, and Mirtazapine was more often

prescribed for males than females.

For diabetic patients without a history of

depression, larger differences were observed. The prescription frequency

was higher for females than males for each of the individual SSRIs;

Amitriptyline, Nortriptyline and Venlafaxine were more frequently

prescribed for females than males; and Bupropion was more prescribed for

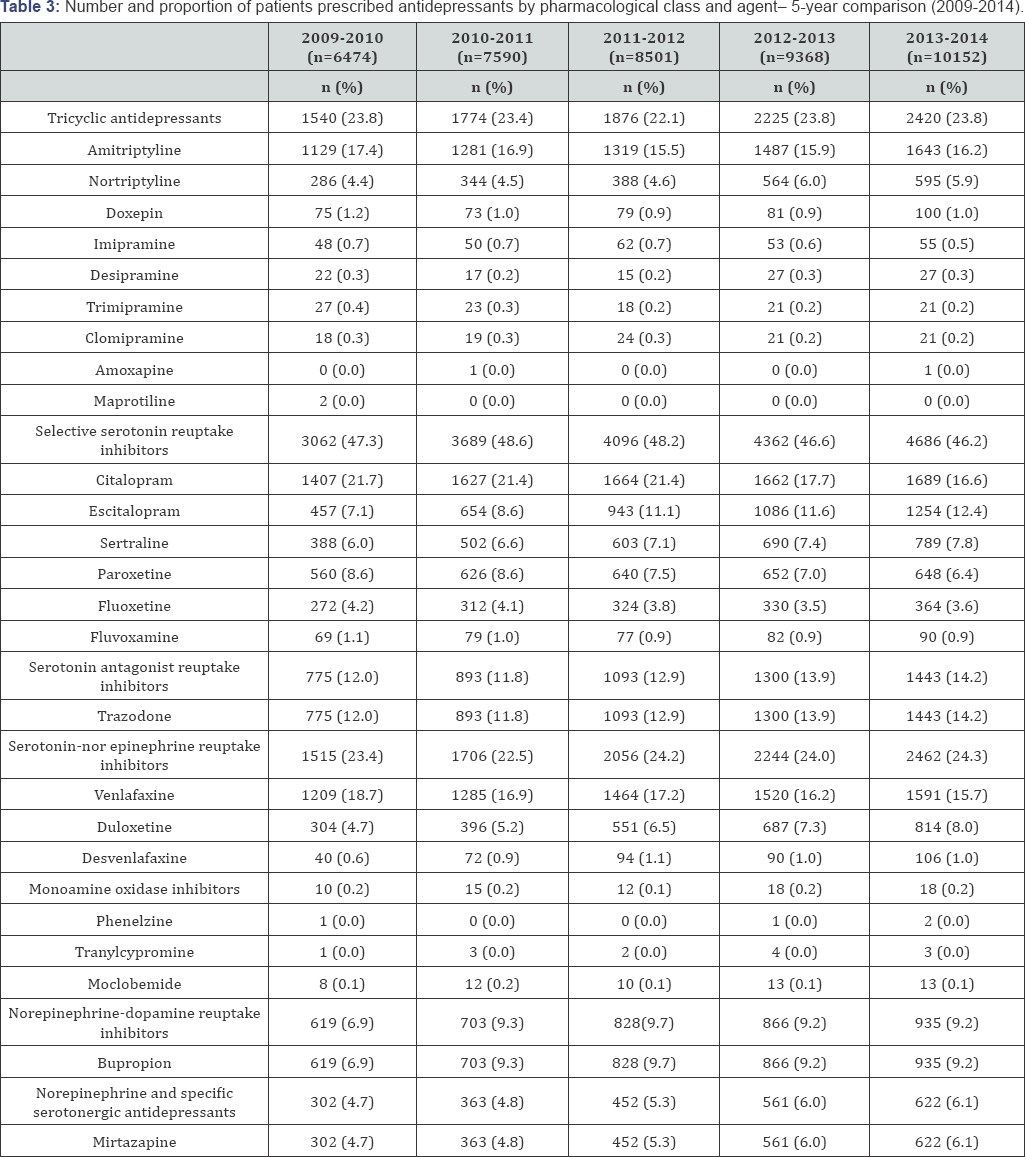

males than females. Table 3

provides a comparison of 5 annual cross-sections of diabetic patients

prescribed ADs between 2009 and 2014. Across the 5-year span, the

relative proportions with which the pharmacological classes were

prescribed remained stable. Changes in proportions were observed for

individual medications within the classes, however. Increases in

relative prescription frequency was observed for Escitalopram,

Duloxetine, Bupropion, Mirtazapine and Trazodone. A decrease was

observed for Citalopram, Paroxetine, Venlafaxine and Amitriptyline.

Discussion

Interpretation

The present study provides a description of AD

prescription in Canada for people with diabetes. This appears to be the

first epidemiological study of primary care practices describing the

prescription of ADs for people with diabetes in Canada. Additionally,

very few studies to date have described the prescription of ADs in terms

of individual medication.

This study's findings regarding the proportion with

which the different classes of ADs were prescribed for people with

diabetes and a history of depression are consistent with other research

using CPCSSN data but described the prescription of ADs in a Canadian

primary care population with a history of depression (with and without

diabetes) [12].

The finding that SSRIs are most frequently prescribed class of AD is

consistent with literature suggesting SSRIs are the standard of care for

depression [19]. Evidence from clinical trials suggests SSRIs and NDRIs may be associated with improved glucose metabolism [7,20,21] and that TCAs and SNRIs may be associated with impaired glucose metabolism [8-10].

The mechanisms explaining these findings are inconclusive, but research

suggests that the ADs binding profiles (the transporter and receptor

affinity) play an important role [13,22,23].

The present study shows that almost half of diabetics prescribed ADs

were given SNRIs or TCAs. While evidence so far is inconclusive, the

frequency with which these ADs are prescribed may be cause for concern

as it appears that primary healthcare providers are not aware of the

negative impact of these medications with regard to glucose metabolism.

Given the similarity in prescription patterns for the general primary

care population with a history of depression [12]

and diabetic patients with a history of depression, it appears that

health care providers’ AD prescription choices are not affected by

current evidence regarding the risks certain ADs pose for people with

diabetes.

This study found that over half of the diabetic

patients prescribed ADs had a history of depression. History of

depression was used to define those for whom ADs were prescribed for the

treatment of depression. The prescription of ADs for people with

depression tended to differ from those without. This is to be expected

as ADs are prescribed for a number of other conditions than depression,

including: general anxiety or panic disorders, obsessive-compulsive

disorder, and eating disorders; and clinically accepted off-label

indications include insomnia, tobacco-cessation, headaches, neuropathic

pain and chronic pain [24].

In patients without a history of depression (and those with a history

of depression but were prescribed an AD for the treatment of another

condition), the ADs were more likely prescribed for other conditions.

The trend of differing prescription frequencies between males and

females for specific ADs is largely related to the frequency with which

these conditions are presented and treated in primary care.

Between 2009 and 2014, an increase in AD prescription

frequency was observed; however, this may be a reflection of gradual

increases participating clinics as well as their data capture. Increases

in relative prescription frequency were observed for Trazodone,

Bupropion and Mirtazapine, for which little research on their effect on

glycemic control has been published. Citalopram and Paroxetine (SSRIs)

decreased in frequency, while Escitalopram, an alternate SSRI,

increased; and Duloxetine (SNRI) decreased while Venlafaxine, an

alternate SNRI, increased. A slight decrease in prescription frequency

was observed for Amitriptyline (TCA), relative to an increase in the

prescription of Nortriptyline, an alternate TCA. Despite growing

evidence that TCAs are associated with impaired glucose metabolism [7,8,25,26] no change in proportional frequency was observed over the course of the five-year observation period.

Limitations

One limitation is that the sample is only somewhat

representative ofthe general Canadian population. In comparison with

2011 Canadian census data, the CPCSSN population in 2013

over-represented older adults and under-represented younger adults; and

the CPCSSN population comprised significantly fewer young adult males

than the general Canadian population [27].

Furthermore, given that the practices participating in the CPCSSN were

not randomly selected, the population may not be generalizable to the

Canadian primary care population [27].

Participating practices tended to be those affiliated with the

practice-based research networks involved in the project and those more

engaged in chronic disease surveillance. Nevertheless, the trends

observed with this sample are expected to compare to those in a wider

population. Future research should seek to confirm this hypothesis.

Second, the case detection algorithms for depression

has a relatively high false positive rate. The case definition for

depression detects lifetime depression, and includes manic disorders and

bipolar mood disorders. Lifetime depression was used in this study to

approximate the prescription of ADs for the treatment of depression as

AD dose and reason for prescription were not consistently recorded or

could not be coded. Patients with a history of depression may be given

ADs for other conditions. For instance, TCAs are more commonly

prescribed insomnia and chronic pain, Mirtazapine is more commonly

prescribed for smoking cessation and Trazodone is more often prescribed

in low doses as a hypnotic [28,29].

Given the number of ADs prescribed to people with depression, use of

lifetime depression as an approximation over-estimates the number of ADs

prescribed for the treatment of depression.

A third limitation of this study pertains to the use

of health records for research. While primary care EMRs permit the

naturalistic examination of prescriptions and health conditions over

time, some values may be missing (not entered or could not be coded) and

some fields may differ between EMR products or may not be used in a

standardized manner by primary health care providers. Were the data

available, AD dose, refer to psychotherapy and diagnoses for other

health conditions for which ADs are prescribed would have been included

to better describe depression treatment practices in primary care

patients living with diabetes.

Conclusion

The present research study provides information on

the prescription of ADs for people with diabetes in primary care

practices. This information is valuable as it provides insight into the

implications of research evaluating the impact of ADs on glycemic

control in people with diabetes. As new and more conclusive evidence on

the effects of ADs on blood sugar emerges, or as new clinical

recommendations are introduced, this study provides the means of

estimating the number of patients that will be affected.

Acknowledgement

JG received a travel award for this research from the

Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR) and a travel award from

the McGill University Department of Family Medicine. SSD is

Chercheur-BoursierClinicien, supported by a Fonds de Recherche Quebec

Sante award. This research was part of the CPCSSN initiative, which is

funded by the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) under a contribution

agreement with the College of Family Physicians of Canada on behalf of 9

practice- based research networks associated with departments of family

medicine across Canada. The views expressed herein do not necessarily

represent the views of the PHAC.

To Know More About Current Research in Diabetes & Obesity

Journal Please click on:

https://juniperpublishers.com/crdoj/index.php

https://juniperpublishers.com/crdoj/index.php

Comments

Post a Comment