Screening and Diagnosis of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: from Controversy to Consensus

Authored by Pikee Saxena

Abstract

Hyperglycemia in pregnancy is associated with adverse

fetal and maternal outcomes. Even lower values of glucose intolerance

have been shown to be detrimental and adverse effects are proportionate

to the plasma glucose levels. However, defining glucose intolerance in

pregnancy has been an issue of considerable debate, and has led to

different recommendations by various authorities worldwide over the last

three decades. Multitude of procedures have been described and glucose

cut offs proposed for the diagnosis of glucose intolerance in pregnancy

have led to considerable confusion. There are a number of controversies

regarding significance of screening for gestational diabetes mellitus

(GDM), universal/selective screening, when to screen and how to

screen-using single or double step, how much should be the glucose load,

how many samples to be taken, fasting or non fasting test to be used.

No single test is superior to the other and the most appropriate test

may be used as per the need and feasibility. These issues will be

discussed in the article.

Abbreviations: GDM:

Gestational Diabetes Mellitus; ACOG: American College of Obstetricians

and Gynecologists; ADA: American Diabetic Association; WHO: World Health

Organization; FIGO: Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics; IADPSG:

International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Group Introduction

Increasing prevalence of diabetes and hence, the ever

increasing ratio of diabetes in pregnancy has led different authorities

worldwide, to suggest various methods for screening of gestational

diabetes mellitus which have been changed several times over last few

decades. According to the principles of screening, the test should have a

high sensitivity, cost effectiveness and be agreeable to the population

under consideration. Traditionally, gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM)

has been defined as an onset or first recognition of abnormal glucose

tolerance during pregnancy [1]. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) still uses this terminology [2].

The disadvantage of this terminology is that it fails to differentiate

between the women who develop insulin resistance during pregnancy from

those who already have preexisting diabetes. Recently, the International

Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Group (IADPSG), the

American Diabetic Association (ADA), the World Health Organization

(W.H.O.) and the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics

(FIGO) have attempted to recognize those women who already have

pre-existing diabetes [3-6]. Hence, the following terms have been coined:

A. Diabetes in pregnancy or pre-gestational diabetes

or overt diabetes: It is diabetes diagnosed during the early pregnancy

or before conception by non-pregnant criteria.

B. Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: Hyperglycemia

recognized in second half of pregnancy and not meeting the criteria for

diabetes in pregnancy. Although GDM shows milder degree of

hyperglycemia, it is associated with adverse maternal and fetal outcome,

not only during pregnancy but is associated with greater chances of

developing type 2 diabetes, hypertension and cardiovascular disease in

both mother and the child later in their lives.

Significance of screening

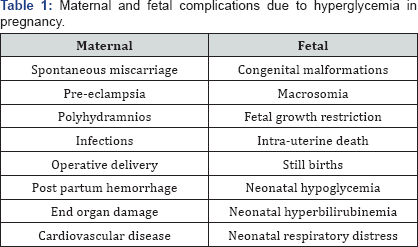

The world prevalence of GDM is 1-28% [7,8]. Several adverse outcomes to the mother and the fetus have been associated with diabetes in pregnancy (Table 1).

These adverse outcomes increase as the maternal plasma glucose level

increase in a continuous manner. Maternal hyperglycemia also affects the

intrauterine environment increasing the probability of the fetus to

develop obesity, hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus later in life

besides the fetal and neonatal complications.Approximately, 50% of the

women who have GDM develop type 2 diabetes mellitus within 20-28 years

of delivery. Early screening and diagnosis GDM not only gives an

opportunity to treat the mother in current pregnancy to avoid maternal

and fetal adverse outcomes, but also to start various strategies to

prevent diabetes in later life.

Whom to screen?

There are two schools of thought regarding screening of diabetes

High risk or selective screening: ACOG [2] and NICE (2015) [9]

support this by assessing the risk factors at the first visit and

recommend selective screening for high risk pregnant women. High risk

factors are-

a. BMI> 30kg/m2

b. Previous macrosomic baby weighing 4.5 kg or above

c. Previous still birth or anomalous baby

d. Previous gestational diabetes

e. Family history of diabetes (first degree relative)

f. High risk ethnic population for DM- African, Asians and

Non-Caucasians

g. History of polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS)

Universal screening: screening of the entire

population or sub group irrespective of the risk factors is advocated by

ADA, IADPSG, W.H.O. and Diabetes In Pregnancy Study group India (DIPSI)

[4-6,8]. Every country should decide whether to follow selective or

universal screening depending upon it's incidence, feasibility and

cost-benefit ratio. In India, universal screening is needed, as Indian

women have 11 fold increased risk of developing glucose intolerance in

pregnancy as compared to Caucasian women [8].

When to screen?

Data from human and animal studies have co-related

the existence of chronic diseases such as obesity, diabetes mellitus and

cardio vascular diseases to the perinatal nutrition [10],

a process known as early metabolic imprinting. It has been observed

that fetal beta cells respond to maternal hyperglycemia as early as 16

weeks and undergo permanent epigenetic changes. Hence, screening in the

first trimester helps to identify those women who already have

pre-existing diabetes to control the sugar levels and avert the

complications by modifying the nutrition and lifestyle at an early

gestation.

a. ADA and IADPSG: Recommend screening at first ANC visit and then at 24-32 weeks in previously undiagnosed GDM

b. DIPSI: Recommends screening at first visit, if normal then at 24-28 weeks and again at 30-32 weeks

c. NICE: Recommends screening at 24-28 weeks in high risk population

d. ACOG: Recommends screening at 24-28 weeks, except in women with high risk factors who are screened at first visit [2].

How to screen and diagnose?

A universal guideline for the ideal screening and

diagnostic method is lacking. A number of methods have been suggested on

the basis of population risks, cost effectiveness but there is a lack

of consensus for the most appropriate universal screening and diagnostic

criteria.

ACOG

Two step procedure:

a. Step 1 Glucose Challenge Test (GCT)/ Glucose

Loading Test (GLT): Patient is given 50 gram oral glucose load

irrespective of last meal. If one hour venous plasma glucose

>140mg/dl, second step with fasting OGTT is done. If one hour venous

plasma glucose is > 200mg/dl, then a diagnosis of diabetes in

pregnancy is made. GCT has a sensitivity of 7088% and specificity of

69-89%.

b. Step 2 Glucose Tolerance Test (GTT): After an

overnight fast of 8-10 hours and three days of unrestricted diet,

fasting plasma glucose is measured following which a glucose load of 100

grams is given orally and blood is then drawn 3 times at hourly

intervals. If patient has any two or more than two deranged values,

gestational diabetes mellitus is diagnosed. Blood sugar value cut offs

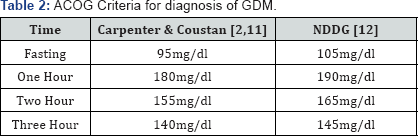

for ACOG are given below in Table 2.

ACOG criteria is based on the risk of development of overt diabetes

mellitus and not on the fetal and maternal outcome. Both Carpenter and

Coustan and NDDG criteria are considered in ACOG. Advantage of 2 step

screening is that not all women have to undergo intensive 3hr OGTT,

where 5 blood samples are drawn. Disadvantage is that patient has to

come for a second visit in a fasting state and therefore may be lost to

follow up especially in developing countries, where 50-60% women receive

antenatal care and about one third are lost to follow up [13]. It is costly and time consuming as five samples are required.

NICE

A woman has gestational diabetes mellitus if she has

either fasting plasma glucose ≥5.6mmol/l or 100mg/dl or 2 hour plasma

glucose ≥ 7.8mmol/l or 140mg/dl after 75g of glucose intake [9].

Although it is a one step screening test, disadvantage is that the

patient has to come for a second visit in a fasting state and may be

lost to follow up.

ADA and IADPSG

Based on the Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes study (HAPO) [14],

cut off levels for diagnosis of GDM were lowered to give an odd's ratio

of 1.75 times the likelihood of adverse outcomes at mean glucose levels

of HAPO study. As shown by HAPO study, adverse pregnancy outcomes, that

is fetal macrosomia, pre-eclampsia, primary caesarean delivery,

neonatal adiposity and cord blood c-peptide levels were noted even below

the threshold of diagnostic criteria of GDM (<95mg/ dl) [4].

ADA and IADPSG recommend the screening during the first antenatal visit

by fasting plasma glucose or random plasma glucose or HbA1c. If fasting

glucose value is 92-125mg/dl, the woman is diagnosed as having GDM. If

fasting glucose ≥126mg/ dl or HbAlc ≥6.5% or random plasma glucose

≥200mg/dl, then the woman is diagnosed as having diabetes in pregnancy [4].

This is followed by repeat screening at 24-28 weeks.

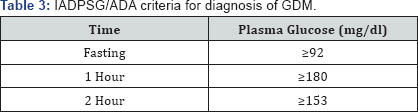

Fasting plasma glucose is measured followed by 75 gram oral glucose load

and plasma glucose is estimated at one and two hours after glucose

load. If any one or more values are deranged, diagnosis of GDM is made (Table 3).

If fasting glucose ≥126mg/dl or any value >200mg /dl, diabetes in

pregnancy is diagnosed. Lowering the thresholds for diagnosis of GDM

would result in increasing the prevalence and hence, the cost of care [2]. Prevalence has increased from 4-7% to 18% by using screening method of IADPSG. Seshiah et al [8]

studied the Indian population and debated that IADPSG had a few

disadvantages. The Asians have higher insulin resistance in pregnancy

and hence increased blood glucose levels, unlike Caucasians on whom HAPO

study was conducted. Most, pregnant women do not come fasting to the

hospital and if asked to come back in a fasting state, the dropout rate

is very high, especially in developing countries. Blood has to be drawn 3

times during the second visit and is cumbersome and time consuming.

HbA1c is an expensive test and is not possible in low resource setting.

DIPSI

recommends universal screening of all pregnant women

in India due to high prevalence of diabetes. A one step screening and

diagnostic procedure with 75gm of oral glucose is advocated during the

first ANC visit, irrespective of the last meal. Venous sample is drawn

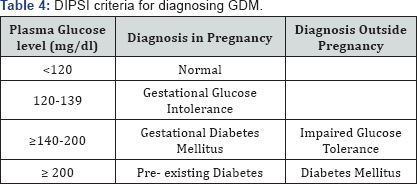

at 2 hours. The criterion for diagnosis of GDM is shown in Table 4. This single step procedure is convenient, highly specific and economical [8,15]. Patient need not be fasting and there is no issue of loss to follow up as patient is screened at the first visit.

W.H.O.

Hyperglycaemia first detected at any time during

pregnancy should be classified as either 'Diabetes mellitus in

pregnancy" or "gestational diabetes mellitus". In 2013, W.H.O. adopted

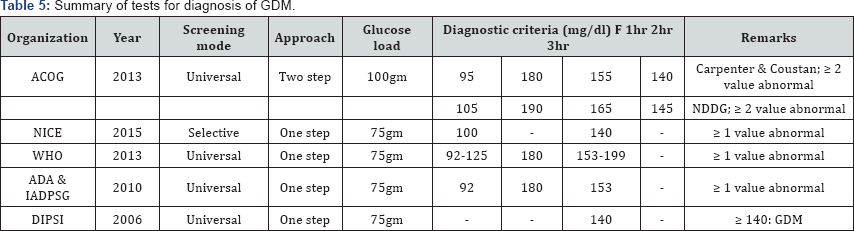

the IADPSG criteria described above [5] (Table 5).

Conclusion

Diabetes in pregnancy whether gestational diabetes or

diabetes in pregnancy have increased in prevalence, may be due to an

altered dietary habits, advanced maternal age of conception and

increased incidence of obesity. It has been seen that an early

management helps to avert these harmful effects. Hence, the need for

screening for diabetes and early diagnosis is of paramount significance.

There is a lack of uniform consensus on the methods of screening and

diagnosis of diabetes in pregnancy. Therefore, physician should choose a

method which is based on the prevalence of diabetes in their

population, it's cost effectiveness and patient compliance. For low and

middle income countries with high prevalence of diabetes, universal,

early screening with a single step, DIPSI criteria seems to be

convenient and highly cost effective.

To Know More About Current Research in Diabetes & Obesity

Journal Please click on:

https://juniperpublishers.com/crdoj/index.php

https://juniperpublishers.com/crdoj/index.php

Comments

Post a Comment